SQL Injection

Many web developers are unaware of how SQL queries can be tampered with, and assume that an SQL query is a trusted command. It means that SQL queries are able to circumvent access controls, thereby bypassing standard authentication and authorization checks, and sometimes SQL queries even may allow access to host operating system level commands.

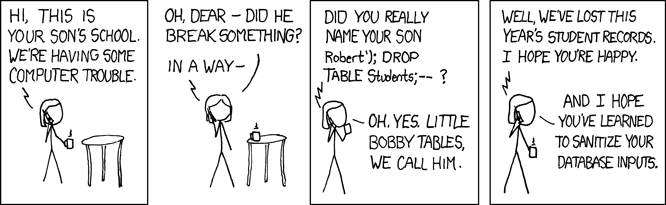

Direct SQL Command Injection is a technique where an attacker creates or alters existing SQL commands to expose hidden data, or to override valuable ones, or even to execute dangerous system level commands on the database host. This is accomplished by the application taking user input and combining it with static parameters to build an SQL query. The following examples are based on true stories, unfortunately.

Owing to the lack of input validation and connecting to the database on behalf of a superuser or the one who can create users, the attacker may create a superuser in your database.

Example #1 Splitting the result set into pages ... and making superusers (PostgreSQL)

<?php

$offset = $argv[0]; // beware, no input validation!

$query = "SELECT id, name FROM products ORDER BY name LIMIT 20 OFFSET $offset;";

$result = pg_query($conn, $query);

?>

0;

insert into pg_shadow(usename,usesysid,usesuper,usecatupd,passwd)

select 'crack', usesysid, 't','t','crack'

from pg_shadow where usename='postgres';

--

Note:

It is common technique to force the SQL parser to ignore the rest of the query written by the developer with -- which is the comment sign in SQL.

A feasible way to gain passwords is to circumvent your search result pages. The only thing the attacker needs to do is to see if there are any submitted variables used in SQL statements which are not handled properly. These filters can be set commonly in a preceding form to customize WHERE, ORDER BY, LIMIT and OFFSET clauses in SELECT statements. If your database supports the UNION construct, the attacker may try to append an entire query to the original one to list passwords from an arbitrary table. Using encrypted password fields is strongly encouraged.

Example #2 Listing out articles ... and some passwords (any database server)

<?php

$query = "SELECT id, name, inserted, size FROM products

WHERE size = '$size'";

$result = odbc_exec($conn, $query);

?>

' union select '1', concat(uname||'-'||passwd) as name, '1971-01-01', '0' from usertable; --

SQL UPDATE's are also susceptible to attack. These queries are also threatened by chopping and appending an entirely new query to it. But the attacker might fiddle with the SET clause. In this case some schema information must be possessed to manipulate the query successfully. This can be acquired by examining the form variable names, or just simply brute forcing. There are not so many naming conventions for fields storing passwords or usernames.

Example #3 From resetting a password ... to gaining more privileges (any database server)

<?php

$query = "UPDATE usertable SET pwd='$pwd' WHERE uid='$uid';";

?>

<?php

// $uid: ' or uid like '%admin%

$query = "UPDATE usertable SET pwd='...' WHERE uid='' or uid like '%admin%';";

// $pwd: hehehe', trusted=100, admin='yes

$query = "UPDATE usertable SET pwd='hehehe', trusted=100, admin='yes' WHERE

...;";

?>

A frightening example how operating system level commands can be accessed on some database hosts.

Example #4 Attacking the database hosts operating system (MSSQL Server)

<?php

$query = "SELECT * FROM products WHERE id LIKE '%$prod%'";

$result = mssql_query($query);

?>

<?php

$query = "SELECT * FROM products

WHERE id LIKE '%a%'

exec master..xp_cmdshell 'net user test testpass /ADD' --%'";

$result = mssql_query($query);

?>

Note:

Some of the examples above is tied to a specific database server. This does not mean that a similar attack is impossible against other products. Your database server may be similarly vulnerable in another manner.

Avoidance Techniques

While it remains obvious that an attacker must possess at least some knowledge of the database architecture in order to conduct a successful attack, obtaining this information is often very simple. For example, if the database is part of an open source or other publicly-available software package with a default installation, this information is completely open and available. This information may also be divulged by closed-source code - even if it's encoded, obfuscated, or compiled - and even by your very own code through the display of error messages. Other methods include the user of common table and column names. For example, a login form that uses a 'users' table with column names 'id', 'username', and 'password'.

These attacks are mainly based on exploiting the code not being written with security in mind. Never trust any kind of input, especially that which comes from the client side, even though it comes from a select box, a hidden input field or a cookie. The first example shows that such a blameless query can cause disasters.

- Never connect to the database as a superuser or as the database owner. Use always customized users with very limited privileges.

- Use prepared statements with bound variables. They are provided by PDO, by MySQLi and by other libraries.

- Check if the given input has the expected data type. PHP has a wide range of input validating functions, from the simplest ones found in Variable Functions and in Character Type Functions (e.g. is_numeric, ctype_digit respectively) and onwards to the Perl compatible Regular Expressions support.

-

If the application waits for numerical input, consider verifying data with ctype_digit, or silently change its type using settype, or use its numeric representation by sprintf.

Example #5 A more secure way to compose a query for paging

<?php

settype($offset, 'integer');

$query = "SELECT id, name FROM products ORDER BY name LIMIT 20 OFFSET $offset;";

// please note %d in the format string, using %s would be meaningless

$query = sprintf("SELECT id, name FROM products ORDER BY name LIMIT 20 OFFSET %d;",

$offset);

?> - If the database layer doesn't support binding variables then quote each non numeric user supplied value that is passed to the database with the database-specific string escape function (e.g. mysql_real_escape_string, sqlite_escape_string, etc.). Generic functions like addslashes are useful only in a very specific environment (e.g. MySQL in a single-byte character set with disabled NO_BACKSLASH_ESCAPES) so it is better to avoid them.

- Do not print out any database specific information, especially about the schema, by fair means or foul. See also Error Reporting and Error Handling and Logging Functions.

- You may use stored procedures and previously defined cursors to abstract data access so that users do not directly access tables or views, but this solution has another impacts.

Besides these, you benefit from logging queries either within your script or by the database itself, if it supports logging. Obviously, the logging is unable to prevent any harmful attempt, but it can be helpful to trace back which application has been circumvented. The log is not useful by itself, but through the information it contains. More detail is generally better than less.